re-reading

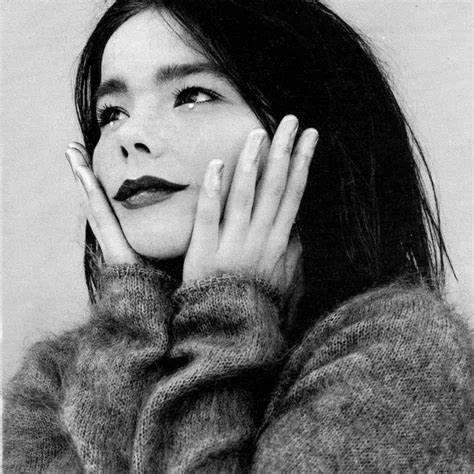

She sleeps because waking

offers no improvement.

Even the sheets

refuse to console her.

Still, how graceful the collapse,

how photogenic the defeat.

The camera loves her

though no one else ever will

St Marks Hotel, East Village c2011 - Medium format film, shot with a Hasselblad 501c.

The Quiet Agony of Internal Isolation

There’s a peculiar kind of loneliness that doesn’t wait for empty rooms or quiet nights. It follows you into birthday parties, group dinners, bars, and late-night laughter. It’s the loneliness of being unseen — not because others aren’t looking at you, but because they’re not really seeing you.

You can be surrounded by people, some of them even close friends, and still feel like a ghost pressing your hand against the glass. You laugh when they laugh. You nod at the right moments. But inside, you are miles away.

This isn’t social isolation. It’s internal loneliness. A condition harder to explain because there’s no visible evidence of it. You can’t photograph it. You can’t treat it with a self-help book or a night out. It lives somewhere deeper — in the disconnection between your outer life and your inner self.

Franz Kafka understood this better than most. In his diaries and stories, there’s a recurring sense of alienation not just from society, but from the self within society. He once wrote, “I am separated from all things by a hollow space… and I do not even reach to its edge.”

Kafka’s characters are often trapped — in surreal bureaucracies, in absurd systems, in grotesque transformations. But the real prison is always internal. That’s the truth many people carry but don’t know how to say: I feel like I’ve disappeared, even when I’m here. Even when I’m smiling. Even when I’m surrounded by people who say they care.

There’s no crisis moment. No dramatic unraveling. Just a slow erosion of intimacy with yourself, until every conversation feels performative, and every relationship feels like it’s happening at a distance. You’re not in the moment — you’re observing it from some dark balcony within your own mind.

We’ve built a world that rewards surface connections and punishes vulnerability. People are trained to hide the ache. To stay strong. To be stoic. But strength, misunderstood, becomes silence. And silence becomes exile.

Kafka understood that language can be both a lifeline and a labyrinth. He wrote obsessively in the night, not because he had answers, but because he couldn’t stand the silence. He was writing against the void. And maybe that’s what we all need to do in some way — speak, write, cry, create. Not to solve the loneliness, but to give it shape. So it doesn’t devour us from the inside out.

Because the loneliest place on earth isn’t a cabin in the woods or an empty apartment. It’s a crowded room where no one knows who you really are.

If you’ve ever felt this way — invisible among the living — you’re not alone. And neither was Kafka.

Now I Know How Joan of Arc Felt

On Morrissey, martyrdom, and the price of honesty

There’s a line in Morrissey’s Bigmouth Strikes Again that’s always haunted me:

“Now I know how Joan of Arc felt.”

It’s half a joke, half a confession. Delivered with sarcasm and a touch of camp, yet underneath it all — it’s deadly serious.

Because if you’ve ever said too much, revealed too much, or simply been too much for this world — you know exactly what he means.

Joan of Arc was burned at the stake. For what? Hearing voices. Following her convictions. For refusing to be quiet, obedient, or ordinary.

Sound familiar?

We don’t burn people at the stake anymore.

We just ignore them. Mock them. Cancel them. Starve them of attention.

We exile them quietly, socially — one eye roll, one unfollow, one “he’s a bit much” at a time.

For artists, this is the tax on authenticity. Speak your truth, and you risk being misunderstood. Say what you really feel, and you’ll be labeled difficult, dramatic, delusional.

Morrissey knew this all too well.

He is the bigmouth who strikes again — every time he opens his mouth, someone’s offended. But at least he says something. Something real. Something risky.

That line — “Now I know how Joan of Arc felt” — is about more than martyrdom.

It’s about isolation. About saying what needs to be said and watching the world punish you for it. About the loneliness that comes from not playing along.

And still… we keep speaking.

Because silence isn’t salvation.

And if they’re going to light the match, at least we go down with something worth burning

The Velvet Underground, Heroin, and the Ghosts of St. Marks Place

There was a time when New York didn’t just tolerate chaos — it thrived on it.

The East Village wasn’t yoga studios and overpriced oat milk lattes. It was junkies, poets, punks, and painters. It was beautiful and broken. You could stumble out of a dive bar on St. Marks Place and find yourself face-to-face with genius — or danger. Sometimes both.

Heroin by The Velvet Underground wasn’t just a song. It was a confession. A lullaby from the gutter. A musical painting of a city teetering between art and oblivion.

Andy Warhol understood that. He saw the art in self-destruction, the poetry in collapse. He took The Velvet Underground and turned them into a living installation — part band, part performance piece — under the banner of his “Exploding Plastic Inevitable,” staged right here in New York. A wild fusion of light, film, music, and madness.

This wasn’t entertainment. It was experience. Art as life. Life as risk.

That world is mostly gone now. Sanitized. Commercialized. But for a few minutes, if you listen close, you can still hear the drone of Lou Reed’s guitar bleeding through the bricks of Avenue A.

The Fall of the East Village

I walk down Saint Marks Place now and barely recognize it.

What used to be punk rock and poetry, dive bars and dirty glamour, is now frozen yogurt shops, overpriced ramen, and guys in Patagonia vests talking about crypto portfolios. It used to smell like clove cigarettes and spray paint. Now it smells like lavender oat milk.

The East Village was never supposed to be clean. It was supposed to be alive—raw, unpredictable, dangerous in a beautiful way. You didn’t come here to feel safe. You came here to feel something.

Back then, Saint Marks was the center of it all. You had kids sleeping in Tompkins Square Park, bands playing in basements, and poets screaming into microphones in tiny backrooms lit by neon beer signs. You had the ghost of Warhol walking these streets, Lou Reed in the shadows, the Velvet Underground on the jukebox. This wasn’t nostalgia—it was now. It was happening.

And yeah, it was chaotic. There were needles and broken glass. There were overdoses and arrests. But there was art. There was life. It wasn’t curated. It wasn’t branded. It was just real.

Now? Hedge fund guys moved in and called it “gritty” in their listings. They gentrified the grit. And the landlords? They saw dollar signs and forgot about community. The rents went up, the culture went out, and what’s left feels like a museum exhibit curated by someone who never lived it.

But a few of us are still here. The ones who survived the noise, the drugs, the heartbreak, the beauty. The ones who still remember CBGB. The Pyramid Club. Trash and Vaudeville before it moved. Max’s Kansas City even though it technically wasn’t here—we felt it anyway.

We remember the East Village before it got a PR team.

I’m not saying everything back then was perfect. It wasn’t. A lot of it was broken. But the brokenness meant something. It had character. It had soul. And these new buildings going up? They’ve got none. Just glass and cold air.

Maybe this is just what happens. Cities change. Scenes die. People grow up. But damn… it didn’t have to happen thisfast. And it didn’t have to become so boring.

Still, every now and then, you’ll spot someone who gets it. An old punk in a leather jacket walking out of a bodega. A kid reading Ginsberg on the corner. A flyer for a band you’ve never heard of stapled to a street pole that hasn’t been yuppified yet.

It’s not completely gone. Not yet.

But it’s fading. And those of us who remember have a duty to keep telling the story. Not for the sake of nostalgia—but to remind the world what real looked like. What it felt like.

We were here. We are here. And no amount of luxury condos will erase that.

~John Kobeck 2025

The Quiet Side of Punk

Punk gets remembered for the chaos — the safety pins, the spit, the sneer. But what I’ve always loved most is the vulnerability buried underneath. The moments when the shouting softens, and something close to confession slips through the distortion.

Songs like “Did You No Wrong” don’t explode — they simmer. They ache. It’s not rebellion for the sake of rebellion, it’s restraint that hurts more than rage. A strange kind of grace hidden behind the noise.

Punk was never just about volume. It was about truth — even the uncomfortable kind.

Tread Softly - I'm still Dreaming

---

“But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.”

— W.B. Yeats

The Weather Inside Me: On Listening to Björk

Some artists sing.

Björk summons.

Her voice doesn’t ask to be understood — it dares you to feel.

Something ancient, fragile, and wild.

Like standing barefoot in the rain, trying to remember what love felt like before the world made you cautious.

She doesn’t craft songs — she builds elemental landscapes.

Volcanoes. Tectonic shifts. Melting glaciers of emotion.

Each track is weather: not something to follow, but something to survive.

There’s rage in her tenderness.

There’s prayer in her chaos.

Even her silence feels like thunder gathering on the edge of a map.

I don’t know how many nights I’ve listened to Vespertine like a secret I didn’t know I was allowed to keep.

Or how often Hyperballad has broken my heart with that line about throwing things off the cliff — just to see what it feels like to let go.

She reminds me that art isn’t meant to be digestible.

It’s meant to wake the animal in us.

The water. The wire. The wish.

Björk is not just music.

She’s the soundtrack of interior worlds — the kind you don’t show anyone.

Unless they already understand.

And maybe that’s why we find each other —

those of us who carry too much weather inside.

Maybe that’s what makes her music so necessary —

She doesn’t offer comfort.

She offers truth.

Emotional landscapes, carved by sound.

And some of us are still learning how to walk through them.

"Emotional landscapes / They puzzle me..." — Björk, Jóga

A Punk Rock Bar in the Middle of Corporate Hell

There’s something jarring — almost surreal — about finding a graffitied punk rock bar nestled between the glass facades of Midtown Manhattan. Strange Love NYC, located on 53rd Street between Second and Third, is a holdout. An echo. A glitch in the matrix. A space that shouldn’t exist — and yet defiantly does.

In a city where even the dive bars have brand managers, where aesthetic rebellion is repackaged and sold back to us as curated grunge, walking into a real punk bar feels like stepping into a time machine. Or maybe more accurately, into a moment of resistance. A refusal. A middle finger aimed squarely at the sterile, moneyed absurdity of contemporary life.

✊ The Aesthetics of Refusal

The bar itself is chaos. Graffiti on the walls, loud punk music blasting through battered speakers, and bartenders who don’t perform hospitality so much as tolerate your presence. It’s everything a Midtown office worker in a fitted blazer is taught to fear — or worse, fetishize.

And yet, for all its noise and grime, the space feels more honest than any fluorescent-lit boardroom or open-plan co-working hive. There’s no pretense of productivity here. No screens. No apps. No performative mindfulness. Just bodies in space, music that refuses to be background, and the anarchic scent of something real.

This isn’t just a bar. It’s what Michel Foucault might have called a heterotopia — a space that functions outside of and in contrast to the dominant social order. Strange Love is not “useful.” It doesn’t optimize your workflow or add value to your brand. And that’s exactly why it matters.

🏢 Corporate Hell and the Spectacle

To stand in Strange Love with a $6 beer in hand, surrounded by sweat and distortion pedals, is to realize how anesthetized the world has become. Guy Debord warned us of this — the society of the spectacle, where all social life is reduced to appearance, to image, to endless representations. Everything is branding. Everything is content.

And punk? Punk was never content. It was confrontation. It was ugly. It was inconvenient. It was, in its purest form, a philosophy of subtraction: subtract respectability, subtract safety, subtract structure — and see what remains.

Now we live in a world where rebellion is neatly packaged by ad agencies and sold to us through ironic slogans on $200 hoodies. Where protest is aestheticized but not practiced. Where we scroll through curated nihilism while sipping oat milk lattes.

In this context, Strange Love doesn’t just feel like a bar. It feels like a last stand.

💀 Punk as Philosophy

Punk has always been more than music. It’s a metaphysical posture — a rejection of the polite lie that things are okay. A Nietzschean scream against the Apollonian order of corporate culture, in favor of the Dionysian chaos of lived experience. It is, in its most distilled form, anti-structure.

But now we live in an age where even chaos is simulated. Where curated authenticity has replaced spontaneity. Where TikTok trends flatten everything into content categories and Spotify algorithms ensure that even your rebellion fits a mood playlist.

To walk into a bar like Strange Love is to remember that there once was — and still might be — a different way of being. One that isn’t filtered, packaged, optimized, or monetized. One that is dirty, loud, and ungovernable.

And maybe that’s why the bar feels so alive. Because it shouldn’t be there.

🧠 On Alienation and Place

There’s a strange kind of alienation in our hyper-modern world. It’s not the alienation Marx described — not just the worker from the product — but the individual from place. From experience. We live in cities we barely touch. We walk past buildings we’ll never enter. We sit in sanitized spaces that erase any trace of the people who were there before us.

Strange Love is the opposite. Every inch of it bears the marks of bodies, of stories, of rage and release. The graffiti is layered. The stickers are peeling. The floor is scuffed. And in that mess, there’s meaning.

Walter Benjamin once said that to experience the aura of a place is to feel its uniqueness — its presence in time and space. In a city that’s rapidly losing its aura to chain stores and glass towers, Strange Love glows like a dying star.

🚬 The Last Real Room

As I stood there — a bald guy with an MFA and a head full of regrets — I couldn’t help but think:

This bar is what art school never prepared me for.

This noise is what museums can’t contain.

This feeling — this aliveness — is what we’re all chasing but rarely find.

Strange Love doesn’t pretend to have answers. But it asks a better question than most institutions ever dared:

What if we stopped pretending?

What if we stopped pretending to be okay?

To be productive.

To be normal.

To be clean.

Maybe, in this punk rock bar in the middle of corporate hell, we remember something ancient: that rebellion isn’t about winning. It’s about refusing to surrender.

And maybe that’s all we really need to do sometimes.

Refuse.

Resist.

Drink a cheap beer.

And scream into the void.

With company……….

The most dangerous weapon isn't a sword. - its a man who enjoys his own company," - Nietzsche

The Most Dangerous Weapon Isn’t a Sword — It’s a Man Who Enjoys His Own Company

— Nietzsche (attributed)

We live in a world addicted to noise.

Podcasts, group chats, social scrolls, breaking news — distraction has become the drug of choice. We fidget when it’s quiet. We flinch when we’re alone. Most people will do anything to avoid sitting in silence with their own thoughts. But every now and then, someone doesn’t run from the solitude. They embrace it. And that person becomes powerful.

There’s a quote circulating online, often attributed to Nietzsche:

“The most dangerous weapon isn’t a sword. It’s a man who enjoys his own company.”

Whether or not he said it is up for debate — but the truth in it is undeniable.

Solitude as Strength

In a society that confuses busyness with worth, stillness becomes rebellion.

The man who enjoys his own company is not lonely — he is sovereign. He is not bored — he is free. He doesn’t seek validation from the crowd because he’s already found something deeper: self-knowledge.

Most people are terrified of who they are when the noise fades. They avoid mirrors, both literal and metaphorical. But the man who welcomes that stillness? Who walks headfirst into the quiet and says, “Let’s see what’s in here” — that’s a man who cannot be manipulated.

You can’t sell him things to make him feel whole.

You can’t shame him into conformity.

You can’t distract him, because he’s already paying attention.

He is the weapon — and the war is within.

Society Fears the Self-Reliant

Our systems don’t want you self-sufficient.

They want you anxious, dependent, scrolling endlessly for a sense of meaning.

Why? Because someone who needs nothing is uncontrollable.

Someone who finds peace in solitude is immune to propaganda.

Someone who no longer needs the crowd… can finally see through it.

Nietzsche understood this. His philosophy was about the individual rising above the herd — becoming the Übermensch. Not in dominance over others, but in transcendence of the need for approval.

Loneliness vs. Aloneness

Don’t confuse this power with isolation.

There’s a difference between being alone and being lonely.

Loneliness is a hunger.

Aloneness is a feast.

Loneliness seeks noise to fill a void.

Aloneness listens to silence and calls it music.

To enjoy your own company doesn’t mean rejecting people — it means you stop begging for their acceptance. You enter relationships as a whole person, not a half looking to be completed. That’s where real connection begins.

The New Warrior

Today’s warrior isn’t armed with steel.

He’s armed with silence.

He doesn’t march — he watches.

He doesn’t shout — he understands.

In a world of compulsive dopamine and artificial validation, the man who can sit quietly, read a book, stare out the window, and be completely at peace — that man is dangerous. Because he can’t be controlled.

Because he’s already free.

Final Thought

If you want to become dangerous — not in violence, but in resilience —

turn off the noise.

Sit in the quiet.

Face yourself.

And then, when you emerge, you’ll understand what Nietzsche was really getting at.

Not swords.

Not fists.

Not armies.

The most dangerous weapon…

is a mind that knows itself

and a man who doesn’t fear being alone.

Note: when I say “man” here I mean man or woman.

The Last Painter of Ideas

Frank Stella has always been one of my favorites—not just for his technical brilliance, but for his uncompromising intellectualism. The Black Paintings, in particular, stand as some of the most conceptually rigorous works of the 20th century. Minimal but not minimal for effect—they were architectural, structured, and deeply rooted in thought. They weren’t trying to seduce you. They were statements.

Decades ahead of their time, these works rejected expressionism without rejecting seriousness. They made form into argument, surface into philosophy.

Though born in Boston, Stella had a distinctly New York sensibility—fast, dry, unsentimental. You can hear it in his voice and see it in his lines.

He may well be the last major American artist who painted with a commitment to intellectual content over visual appeal. Today’s art world too often privileges aesthetics—slick surfaces, Instagrammable installations—over depth. Stella did the opposite. He painted thought. Sadly today, much of so called “fine art” is solely focused on aesthetics, with no real substance or thought behind the work.

NYC Pride March

A few years ago I was hired to shoot the annual Pride March in NYC. I had Press Credentials which gave me access behind police lines.

We Celebrate Stupidity: How Anti-Intellectualism Won

There was a time when to be educated was something sacred. When to quote poetry, to ponder philosophy, to discuss art history over coffee wasn’t pretentious — it was aspirational.

But that time has passed.

We now live in an age where ignorance is a performance, and it’s rewarded. Online, stupidity gets engagement. In politics, it gets votes. In culture, it gets applause.

The Death of Depth

Today’s conversations aren’t driven by truth, complexity, or thoughtfulness — they’re driven by clicks and algorithms.

Long-form thinking has given way to 15-second videos, academic rigor replaced by viral outrage. And we celebrate this shift as if it’s progress.

An MFA today isn’t a badge of honor — it’s often treated like a joke.

Why read Yeats when you can scroll TikTok? Why study history when you can just Google a meme?

As someone who pursued graduate studies in the arts not to make money, but to become a better thinker and human being, this cultural nosedive is painful to watch.

Education Is No Longer About Becoming Educated

Today’s education system is transactional. You get a degree to get a job.

The deeper, classical idea — of education as a moral and intellectual awakening — is gone.

Ask a teenager today what they want to be, and if they answer “a poet” or “a philosopher,” they’ll be met with laughter or concern.

Because in a hyper-capitalist culture, usefulness is the only virtue. If it doesn’t make money, it doesn’t matter.

But must everything be monetized to have value?

The Cultural Shift to Anti-Thought

You’ve probably seen it — crowds twerking in the street, videos celebrating ignorance, movements driven more by emotion than analysis.

There’s a rejection of standards, of nuance, of art for art’s sake.

And before you accuse me of elitism — this is not about taste.

It’s about the loss of curiosity. The decline of reflection. The abandonment of the intellectual life.

Romanticism in a Mindless Age

I’ve always seen the world through the lens of mortality, empathy, and beauty. As a child, I was obsessed with death — not out of fear, but wonder. I devoured poetry, longed for the sublime, and mourned even the pain of strangers.

Today’s world doesn’t understand that kind of sensitivity. It mocks it.

But I believe we need more Romantics, not fewer.

Morrissey once sang:

“It takes strength to be gentle and kind.”

Strength, indeed. Especially now.

Why Western Civilization Still Matters

The canon of Western art, philosophy, and literature is not above critique — but it is the foundation of much of what we call the humanities.

To discard it entirely is to unmoor ourselves from context, from history, from depth.

We are not more advanced than our ancestors. We are simply louder, faster, and shallower.

Look around — does this feel like progress?

A Terrible Beauty Reversed

W.B. Yeats wrote in Easter 1916 of a “terrible beauty” being born.

He was referring to transformation, to revolution, to passion erupting into the world.

Today, something else is being born — or maybe something is dying.

The arts are no longer sacred. The intellect is no longer admired.

We are surrounded by noise, but starved for wisdom.

And unless we course-correct, the celebration of stupidity may become the only tradition we have left.

Final Thought

This post isn’t a cry of superiority. It’s a plea.

For dialogue. For curiosity. For remembering that being smart, thoughtful, and open-hearted isn’t something to be mocked — it’s something to be honored.

Because a culture that rewards stupidity will eventually forget how to be anything else.

“Everything is art, because nothing is” - Sir Roger Scruton

I Won’t Be Here Forever—And Neither Will You

Reflections on “The Conqueror Worm” by Edgar Allan Poe

I won’t be here forever, and neither will you.

That fact doesn’t scare me—it humbles me. It reminds me to pay attention, to savor what is passing, because everything is passing.

One poem captures this better than anything I’ve ever read. It’s by my favorite poet, Edgar Allan Poe. In The Conqueror Worm, Poe strips away all illusion and reveals the one unshakable truth: life is a brief, tragic performance, and death—the silent, patient conqueror—always takes the final bow.

There’s no comfort in this poem, no promise of redemption. Just the brutal beauty of mortality laid bare. It’s honest. It’s haunting. It’s timeless.

Here is the poem:

The Conqueror Worm

By Edgar Allan Poe

Lo! 'tis a gala night

Within the lonesome latter years!

An angel throng, bewinged, bedight

In veils, and drowned in tears,

Sit in a theatre, to see

A play of hopes and fears,

While the orchestra breathes fitfully

The music of the spheres.

Mimes, in the form of God on high,

Mutter and mumble low,

And hither and thither fly—

Mere puppets they, who come and go

At bidding of vast formless things

That shift the scenery to and fro,

Flapping from out their Condor wings

Invisible Wo!

That motley drama—oh, be sure

It shall not be forgot!

With its Phantom chased for evermore

By a crowd that seize it not,

Through a circle that ever returneth in

To the self-same spot;

And much of Madness, and more of Sin,

And Horror the soul of the plot.

But see, amid the mimic rout

A crawling shape intrude!

A blood-red thing that writhes from out

The scenic solitude!

It writhes!—it writhes!—with mortal pangs

The mimes become its food,

And the angels sob at vermin fangs

In human gore imbued.

Out—out are the lights—out all!

And, over each quivering form,

The curtain, a funeral pall,

Comes down with the rush of a storm,

While the angels, all pallid and wan,

Uprising, unveiling, affirm

That the play is the tragedy, “Man,”

And its hero the Conqueror Worm.

Somewhere between glam rock and grit — a summer snapshot from St. Marks Place, East Village. c2014